There’s a bottle shop in Durham, North Carolina perfectly situated between a busy commercial block and Duke University. Shopping selections can be pretty diverse among customers. College students can pop in for 30-can cases of Natty Ice while beer geeks can buy $40 single bottles of Oxbow, Fonta Flora, and The Lost Abbey. There’s plenty of middle ground, too, with local and regional craft beers side-by-side with nationally-known brands, all competing for attention as shoppers pace through aisles, necks craning up and down to see the top of a seven-foot shelf down to bottles near their feet.

“It’s our responsibility to start thinking outside the little craft circle that we once started in,” Founders Brewing CEO Mike Stevens said at a June 2017 Brewbound Session event, mentioning the importance of larger brewers helping to broaden beer’s consumer base in order to help up-and-coming brewers get stronger foothold in the industry. He continued:

“Do we need to start looking at consumers outside of that small bubble? Do we need to start thinking about what those price points need to look like? What those beer styles need to look like? And do we have to start appealing to a broader audience?”

Stevens should know. It was his company’s move to shift All Day IPA to 15-packs at 12-pack pricing that was ahead of similar moves by New Belgium, 21st Amendment, and others. With help from its package size and price, All Day has become the top-selling canned craft beer, according to IRI’s multi-outlet and convenience retail channel universe (MULC), and is a top-three IPA overall.

In recent years, Narragansett Beer has made its living off this combination of quality, quantity and price point, more than tripling production and revenue between 2010 and 2016 led by its Lager, which retails for $5.99 to $6.99 per four pack of 16-ounce cans. Seasonals or limited releases may cost more, but a brand like Narragansett’s Del’s Shandy still costs a suggested price of $9.99 to $10.99 for a six pack of 16-ounce cans. To get granular, that’s a difference of roughly three cents/ounce of Narragansett’s six pack versus a six pack of 12-ounce beers at the same price.

Of course, not everyone sees the benefit of lower costs.

“The consumer may or may not look at that as price degradation because they may be looking at the cans and thinking, well, that’s kind of equivalent to a 12-pack of bottles, except they’re getting three free beers,” Boston Beer founder Jim Koch told Brewbound in April 2017, noting 15-packs can create a “downward pressure on price.” “So I don’t see an industry cost structure and cost curve that would support a lot of downward pricing without taking out a big piece of the back end of this supply curve.”

But the fact of the matter may be that it’s already too late.

Macro beer’s biggest names—Bud Light, Coors Light, Miller Lite, and Budweiser—are suffering to various degrees, and as more expensive craft beer has boomed in recent years, some lower priced brands are seeing a mini resurgence as well.

Miller Lite is the only beer of the top-four selling brands to have seen dollar sales growth in the five-year period between 2013 and 2017, receiving a 5.8% bump in IRI MULC stores during that period. Over that time, two lower-cost regional brands, Rainier (+80%) and Lone Star (+58%), have flourished. Even Busch Ice has continued a steady climb (+56.7%).

While beer’s “high end” price point has shown strong growth (as has the equivalent for wine), there’s still a war to be won across a variety of tiers. MillerCoors is launching its own salvo with Two Hats, a new, flavored beer brand that uses the slogan "GOOD CHEAP BEER" on promotional materials. The goal of the brand is to specifically attract price-conscious, Generation Z consumers, people who are drinking less beer than other age groups. Two Hats will carry a suggested retail price of $5 for a six pack of 16-ounce cans.

“There haven’t been any new mainstream light beer launches for this group at this price point…so it’s no surprise they think of beer as dusty and old and migrate to wine and spirits,” Justine Stauffer, brand manager for MillerCoors in charge of the launch of Two Hats, told the company’s blog. “With Two Hats, our goal is to build the next generation of beer drinkers. This is a beer they can get behind because it offers drinkers what they want: A great beer at a great low price.”

And it’s not just Big Beer that sees price as a point of contention. Oskar Blues just recently announced a lower pricing for its G’Knight Imperial Red IPA, dropping to retail in the $8.99-$9.99 range. Two Roads is also utilizing new price management software to assess opportunities in pricing and promotions because "there is more pricing complexity than ever before," COO Clement Pellani told Brewer Magazine.

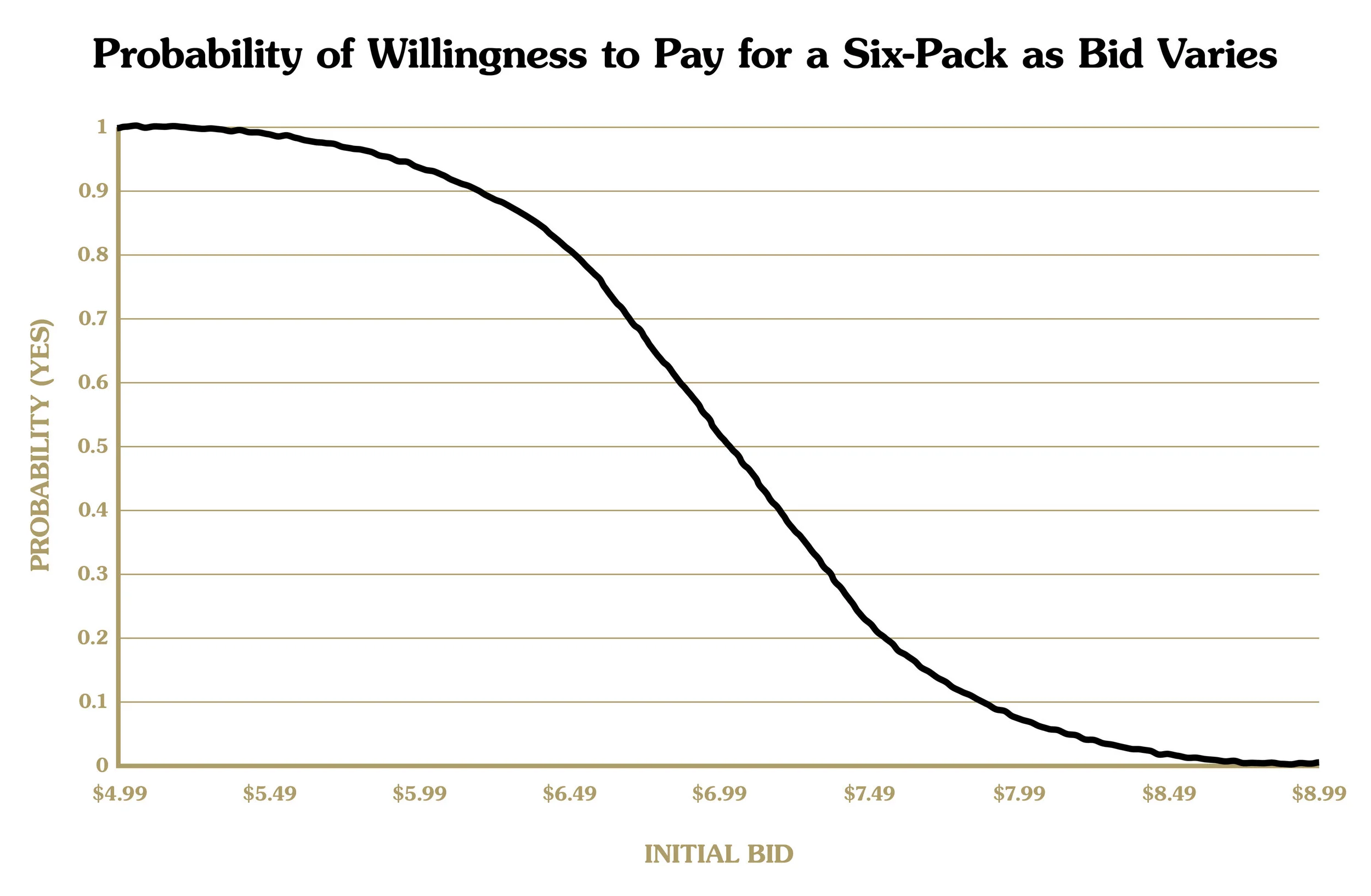

Which is why it makes sense that more breweries explore the thresholds of what can be afforded by them as well as what can be afforded by their consumers. By showing a willingness to make margins tighter, breweries are expanding their potential reach. According to Nielsen research, the price sensitivity for a six pack will weed out some buyers as soon as it crosses the $6.99 barrier. At that price, 12% of buyers will no longer pay for that brand, a percentage that increases by another 6% at $7.99 and an additional 7% at $8.99.

The elasticity of beer pricing—for each drop in cost there is an uptick in volume sold—plays an important psychological part in sales. In a two-part series last year, The Sacramento Bee’s Blair Anthony Robertson explored pricing of local craft beer, to which he found support and dismay over prices that get as high as $24 for a four-pack of cans. In a text from A.J. Tendick, a co-owner of Bike Dog Brewing, a 15-barrel brewhouse in Sacramento, Tendick noted awareness of today’s price structure:

“We are releasing Dog Years IPA next month in cans (4 x 16 oz.) and had an internal discussion about not pricing people out, trying to keep craft beer approachable and affordable, and got it priced so it should sell at $10.99 in stores. You read our minds.”

Price, of course, becomes a determining factor at some point for all consumers. One study by researchers at Washington State University cited reasons for paying more for beer included income (higher, more willing), age (younger, more willing) and frequency of consumption (more often, more willing). Taste, price, and brand were cited as the most important attributes by participants, in that order. They explain that craft brewers have the ability to demand higher prices based on preferences toward taste, but there is a line at which the willingness to pay drops drastically.

Among results, the paper concluded on a sliding scale related to participant’s willingness to pay a certain price for a six pack, which shows a clear decline around $7.

Taking the ranking of characteristics presented by the study, it’s worth considering how taste and price can factor into a consumer’s interaction with beer brands. Because beer is an experiential good and, in most cases, must be purchased before creating a personal opinion on its quality, it falls into a dangerous area where poor experiences can be detrimental to creating return customers. Given the wide range of breweries and brands available, thinking about a six pack in terms of perceived quality-to-price can be a realistic expectation for some beer buyers.

If taste is important, and therefore convinces a shopper to spend a little more, that price point is still not lost on them. To push a customer past their comfort level—in cases of research, somewhere beyond the $7-$9 range—is to take a risk, just like any other product or service. However, because beer options are increasingly plentiful, the marriage of quality and price point is perhaps more important than ever—for better and worse.

“When people see a higher price point, they think 'this thing is better,'” Brewers Association chief economist Bart Watson noted on the GBH podcast. “There are caveats, and whenever they try whatever the product is, they may have different opinions, but certainly the opposite effect is true, too. If you start cutting price, people start looking at what other brands are at that price and they start associating it that way."

Which puts price in an odd place. The American economy is soaring, but not for all Americans. With wages essentially stalled, cost is still a front-of-mind issue for many consumers. “Craft” beer has a direct connection to ideas of quality, but that also doesn’t make it impervious to consumer trends. The vast majority of beer drinkers aren’t spending $20 for a four pack of 16-ounce cans, or even close to that. If anything, younger generations are only becoming more frugal and price-sensitive.

Moving forward, the variety of price points will continue to matter, perhaps even more so. Decisions may increasingly come down to better defining a meaning of “value” and whatever subjective application it might have. The challenge for breweries isn’t just about making something good, but the residual effects of what that means for taste buds and wallets alike.

—Bryan Roth