In the age of fake news, everything is made subjective.

Our political climate has led to a daily discussion of what is "real," which is, of course, filtered through the prism of our own bias, experience, and point of view. And that makes for problematic interactions, whether it's an interpretation of what's going on in the world around us, or even talking with friends online or in person. The increased polarization of stances are a sign of the times in which we live—facts don’t always matter as much as our own echo chambers.

“As a result of the vast number of conflicting stories presented in the media’s different mediums, we have begun to confuse our sense of truth and reality making everything seem subjective,” Max de Haldevang wrote for Quartz at the height of the 2016 presidential campaign. When creating our opinions, it's now more commonplace to use available information both inconsistently and incompletely, which detracts from accuracy and the reason why we may seek out help in the first place.

One estimate by the Pew Research Center says 82% of U.S. adults "at least sometimes read online customer ratings or reviews" before buying a product for the first time. The interest and influence for Consumer Reports—which is run by a non-profit!—is waning. Even Nielsen has pointed out that the ”most credible” source of advertising comes from our social circles.

In the age of fake news, we’re all experts. Best (worst?) of all, we’re fueled by the democratizing power of a tiny computer we can hold in our hand. Average Janes and Joes across the country may ultimately have little to do with what happens in their state and national capitols, but we can't overlook the sway they have in whatever self-curated communities they create.

This changes our perception. In a world with no experts or all experts, what is "right" and "wrong" or "fake" and "real" constantly changes depending on who you’re talking to, and that means that purely objective information is up for debate. And if information comes in a list, even if defined parameters are set, we’ve set ourselves up for a battle of wits.

Last week, the Brewers Association, which represents thousands of American "small and independent" beer businesses from coast-to-coast, released its annual record of the top-producing breweries in the country under the title "Top 50 Breweries of 2016."

Uh-oh.

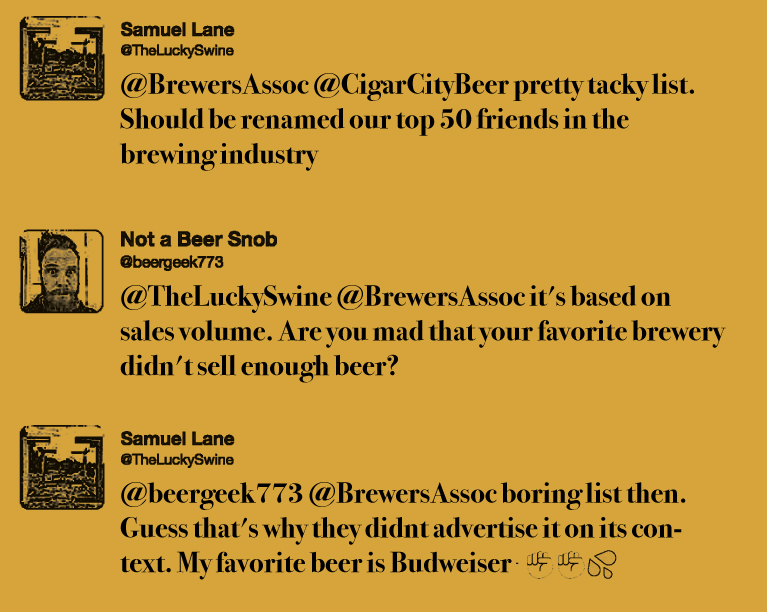

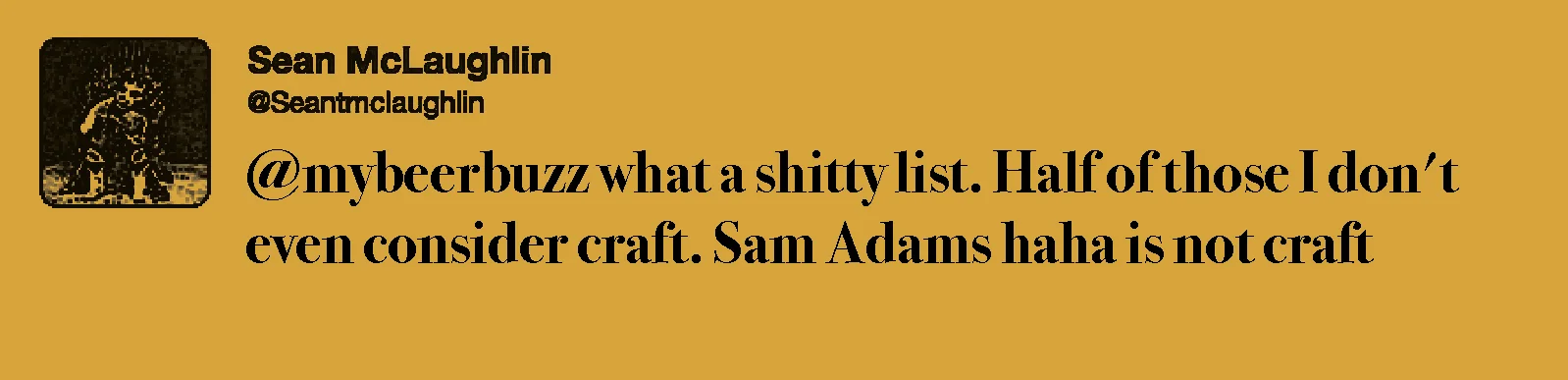

The backlash was swift. Pushback came over social media as commenters offered their hot takes while ignoring the factual basis of the list—it was, as it has been for at least a decade, organized by production levels. Even still, these internet denizens repeatedly asked, as if they were debating a listicle on Reddit, “how can you leave [My Favorite Brewery Name Here] off this list?”

In one Facebook forum, it took a few comments for readers to finally understand the BA’s reasoning, which was mentioned by the organization in the first sentence of the press release.

"WTH? Nothing from NC or Virginia??" one commenter asked. "Snore" was one immediate response. Then: "Although there's a few good ones on there It's seems to be mostly a list of who's producing the most quantity."

Mostly.

Do a Google search for "best brewery in America" and there's a hint to the root of this problem. The results, predictably so, include post after post of opinionated lists, declaring who the "best" brewery is for any given year, each one filled with comments crying foul, asking why a local favorite was left off. Today's beer sin? Assuming anecdote equals data, as if many readers emboldened by their passion for the industry could be persuaded anyway.

Tension among beer geeks isn’t just for the Merriam-Webster lovers who care to debate the definition and philosophy of “craft” in their beer. When everything is a contest, everyone feels like they're the deciding judge.

Perhaps the rate and ease with which we’re encouraged to give our opinion of products, restaurants, and even people is finally catching up to us. In the final three months of 2016, there were 121 million reviews posted on Yelp. Over the course of the full year, TV shows based on audience interactions of rating performers kept America's Got Talent, The Voice, and Dancing With the Stars among the top-20 most-watched shows. Even a terrifying episode of Black Mirror, the hit anthology series that crosses modern technology use with satirical social twists of The Twilight Zone, eerily paralleled a real-life app called Peeple, whose original purpose was to provide numerical ratings of friends and family.

“I don't want you here,” the episode’s antagonist, Naomi, says to “friend,” Lacie. “I don't know what is up with you, but I cannot have a 2.6 at my wedding.”

For better or worse, the evaluating process of our interactions is fixed into the human experience. For decades, we’ve lived by an idiom that instructs us not to judge a book by its cover. Not only is it now easier to do just that than ever before, but we don’t really even have to read the book, either—and we can still quickly go online to tell people what we think about it. Our willingness to share opinion—with or without consideration or tact—is practically conditioned, emphasized with each clickbait headline that arrives online, practically begging for hate-reads and angry reactions.

“Best of” lists have trained us to immediately consider what is missing as much as what’s actually on our screens. So even when we’re presented with objective, defined facts, there’s still muscle memory in place, encouraging twitching fingers toward a keyboard.

In the hours after the “top 50 breweries” release, its problem was exacerbated by others. “Here is a List of the Top 50 U.S. Craft Breweries,” read the headline on CraftBeer.com, a website of the Brewers Association. The title, easily repeated over social media, only worked to stir the angry masses—each with their own subjective list of excellence—further.

Similar behavior was seen months prior, when bottle shop franchise Craft Beer Cellar announced their list of approved beers to sell in stores, based on judgments of quality from store owners and “brand members.”

“Whether it is a local brewery, or one from further afield, one thing is true: it should stand up as the most positively reputable beers that are available in any market a Craft Beer Cellar is located,” CBC co-founder Kate Baker said in a statement.

Again with the lists! Customers cried foul toward the business’ decision on what beers were “positively reputable” or not, even though the decision was made in their best interest. With more than 5,000 breweries in the U.S. alone, shouldn’t it be considered an assist to filter out beers of lower quality? The idea was too much for some. Let the market decide and let consumers tell you how that comes to fruition, with opinion and dollars, they argued.

The number of ways we’re provided and asked to offer feedback makes it easy to stay within echo chambers, nodding in approval when someone “toasts” our check-in on Untappd or writes in awe when commenting on a picture posted of the latest “white whale” beer hunted down and poured into fancy glassware. For those that give it consideration (a small percentage, to be sure!), these actions empower the process, offering greater meaning to an act as simple as drinking a beer. We know how much we’re supposed to care about it, on a scale of 1-5.

Which is why we should have seen this coming with the Brewers Association’s statistically-based list of top production breweries. Facts, once rigid in their truth, are now far too malleable, contorted through our eyes, twisted through our words, and reshaped as personal gospel. What is a “top brewery,” even?

Nobody can be an expert if we all are.